Stagnant Disabled Employment Gap Underpinned by a Lack of Accessible Work Opportunities

Exploring Work and Wellbeing during Mental Health Awareness Week

One of the Labour Government’s most unpopular actions since taking office, arguably only behind the Winter Fuel Allowance cuts, has been the attack on Disability Welfare Benefits.

The government aims to save £5billion by the end of the decade and achieve an overall UK employment rate of 80% in the long term. However while accessible jobs remain scarce, the financially punitive approach risks failure.

The Background:

In March’s Spring Statement, Chancellor Rachel Reeves announced disability-related benefit cuts to the tune of £5billion savings by the end of the decade. The government’s Pathways to Work Green Paper proposes to curb spiralling welfare spending by restricting the health element of universal credit, a subsidy for those with a limited capacity for work, and tightening eligibility criteria for Personal Independence Payments (PIP).

PIP is not a work-related or means-tested benefit. It aims to offset the higher cost of living for disabled people, which the charity Scope estimates to be £975 per month for the average disabled household after taking PIP into account.

The government’s goal is to achieve an 80% UK employment rate, up from 75% currently. In 2023/24, employment rates were 81% for non-disabled people and 54% for disabled people. Aside from some volatility around the Covid-19 Pandemic, the disability employment gap (currently 27%), has been on a sustained but sluggish decline, closing by 5% in the last five years.

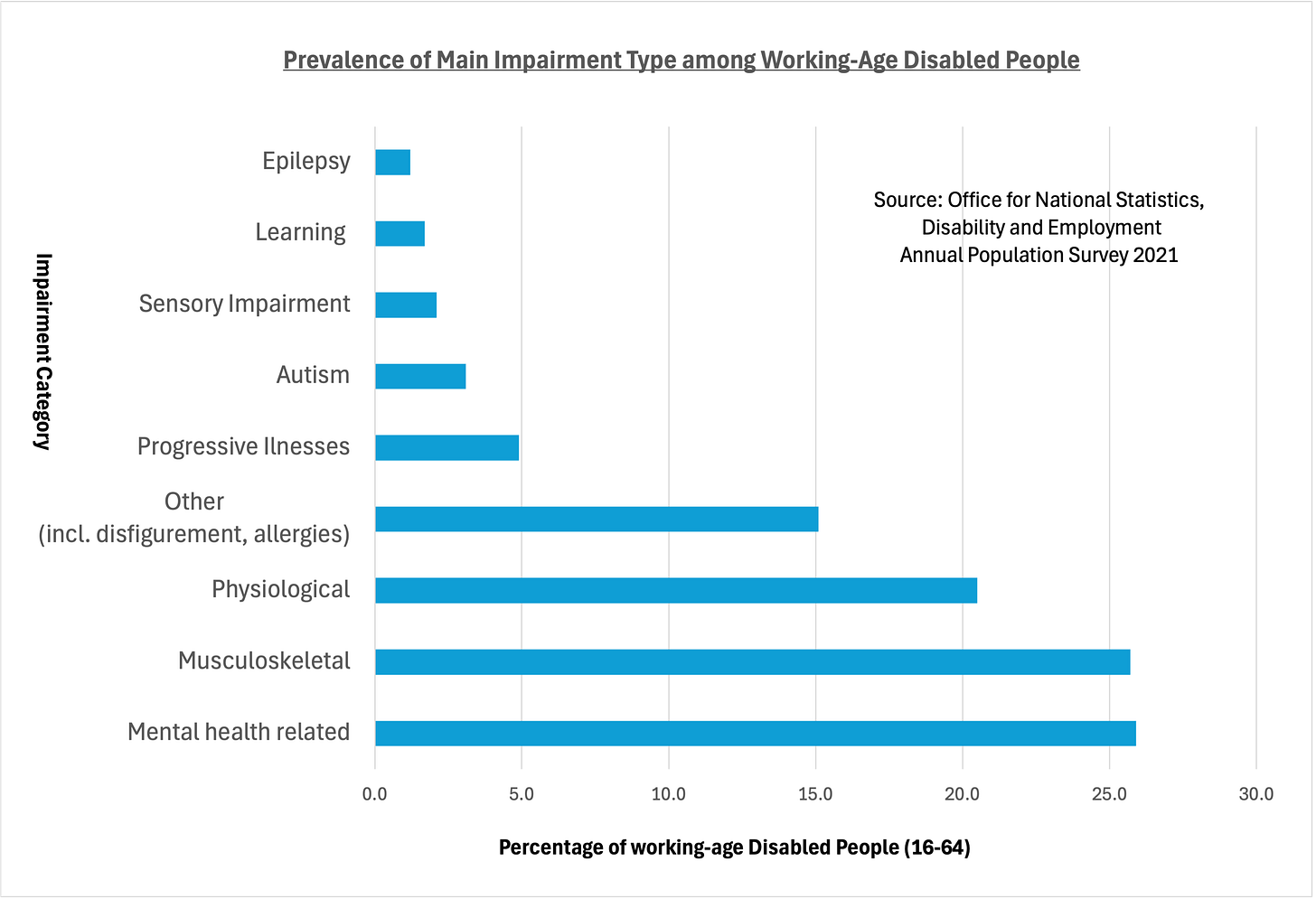

Young people and those with mental health problems are gaining particular government attention. In 2023/24, more than a quarter (27%) of economically inactive people (those not in work or looking for work) had mental health-related conditions. That proportion has almost doubled in ten years, from 14% in 2013/14, as mental health continues to account for a higher proportion of impairments.

The Need for flexibility

Many workplaces are accustomed to considering flexible work arrangements, like part-time or flexible hours, as a perk to be earned through long service or the preserve of working parents. But for many disabled people, flexible working can be essential to filling a position.

The most recent data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) shows that almost a third (31.8%) of disabled workers work part-time, compared to just over one-in-five (21.8%) of non-disabled workers. Fewer working hours can help balance the management of medical and care demands, or reduced energy levels.

However, the latest Timewise Flexible Jobs Index found that just 3 in 10 job adverts mention any kind of flexible working, despite 9 in 10 people wanting flexibility. This may also mean that some disabled people are discouraged from applying to 7 in 10 jobs.

Flexible roles are more common in the lowest pay brackets and less progressive roles. ONS insights show that disabled people are more likely to be in low pay, and less likely to have career progression opportunities, than their non-disabled counterparts. This is despite significant long-term improvement in education outcomes for disabled people, which has seen the number without qualifications fall rapidly and degree attainment rise.

The Hyper-productivity Problem

One person seeking accessible work is job-hunter Jessica, from Salisbury. Despite having a strong degree and being in long-term work previously, she’s been struggling to find a suitable role that will accommodate neurodivergence and mental health issues. She says:

“we're in a slightly more enlightened time with regards to these kinds of issues, but I don't think that has fully translated to the workplace.”

Previously, Jessica’s workplace accommodations have included flexible hours, audio software and deadline adjustments.

“It really is about having that understanding in the workplace. I've been in situations where accommodations have just been ignored and it's had to be escalated. If you have [an employer] who can support you through it, and doesn't just dismiss it, it's so much easier to find solutions.”

She’s currently seeking a part-time job with home working, but without much success.

“I would love to do something more flexible or part time. There's the monetary considerations, because you don't realise what a cut it is of the finances. But I feel like that would give me a bit more balance, maybe to manage my health issues better.

“one thing that's really noticeable now is the lack of hybrid work and work from home, which sometimes make [work] more manageable. It doesn't feel like there's a lot of opportunities that are flexible. There's barely anything that's part time. For some organisations, their culture and attitude is so ingrained.”

“We've also got to be realistic about the attitudes of a lot of hiring managers. There is definitely some bias.”

Jessica believes that the lack of flexible working opportunities is part of a wider cultural problem that may exclude disabled people and mean employers miss out on talent.

“I think as a society, we're pretty obsessed with productivity. We're not machines, but you're expected to be a bit of a robot in the workplace, no matter what's going on with you.

“There are definitely elements of creativity and different thinking that come out of [being neurodivergent']. But it's really hard to foster those talents when they just want as much work out of you on that given day as possible.

“Obviously, it's great if we can be productive all the time. But sometimes we need to slow down. I think we very much have this attitude in Britain of almost taking pride in being a mess because of work. You're actively neglecting your health at times.”

“I'm feeling a little bit apprehensive even now at the thought of going back to that hustle culture. A lot of people are in it, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's right.”

Tight Competition in the Job Market

Job vacancies have hit a 5-year low of 761,000 this quarter, down almost 15% on the year and below pre-pandemic levels for the first time. It comes amid rising employer costs and global economic uncertainty.

In a fierce field of candidates, disabled people may be better educated and more competitive than previously, however they are also more likely to need flexible working and access arrangements. Impairment limitations mean that not every vacant job is an accessible job.

I delved into the government’s own Find a Job website to understand the flexibility and accessibility of current job adverts. I filtered by Disability Confident Employers, a government scheme which employers can enrol on to indicate their readiness to employ disabled people. At the time of writing, just 14% of full-time jobs, and 16% of part-time jobs, were posted by disability confident employers.

Within those roles, I also filtered by flexible working patterns. My search returned underwhelming, if not woefully demoralising, insights.

Of the almost 113,000 total UK jobs on the site, just over 16,000 were with Disability Confident employers. Within those jobs, less than 5,000 (<5% of total jobs) were part-time. Disability confident roles across all working patterns with flexible (hybrid or remote) working styles made up less than 1% of the total UK jobs in every category. Anyone wishing to work in a remote, part-time role with a disability confident employer will have to battle it out for one of just 14 available jobs of the 113,000 we started with. That’s before we consider industry, skill-set or interests.

A Controversial Reception

Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall says that an additional £1billion per year will fund employment support for disabled people by 2030, to boost living standards through employment. However details on the shape and effectiveness of this support are murky and the proposals have triggered uproar from Disability Charities and MPs as well as protests.

James Taylor, Executive Director of Strategy at Scope said of the Government’s budget and proposals:

“The biggest cuts to disability benefits on record should shame the government to its core. They are choosing to penalise some of the poorest people in our society.

We welcome the investment in tailored, non-compulsory employment support. But ripping away £5 billion out of the benefits system by 2030 will completely undermine this positive step.Starting with the amount they want to save, rather than on how to improve the system, spells disaster.”

A recent poll by More in Common found that the majority of Brits (54%) think these disability benefits changes are driven by cost-cutting, while only 32% believe the aim is to encourage employment. A backbench rebellion is brewing over the proposals. A growing number of MPs have signed an open letter which says:

“Whilst the government may have correctly diagnosed the problem of a broken benefits system and a lack of job opportunities for those who are able to work, they have come up with the wrong medicine. Cuts don’t create jobs, they just cause more hardship.”

“We also need to invest in creating job opportunities and ensure the law is robust enough to provide employment protections against discrimination. Without a change in direction, the green paper will be impossible to support.”

The current direction will encounter obstacles such as tackling long NHS wait lists so people in need of treatment can return to work, and the sluggish processing of Access to Work applications. But a deeper shift in the UK job market and work culture is needed if more disabled people are to find appropriate, accessible, long-term jobs. Until that is achieved, the government’s stick-wielding approach, with no carrots to dangle, may prove not only cruel, but foolish.

Jessica reflected on the fallout of disability cuts:

Since these things have been announced, there seems to be quite a lot of negativity about disabled people coming from the general public. It gives me an anxiety that we're sort of going in the wrong direction when it comes to disability.

Disabilities are not going to go away. Neurodivergence is not going to go away. We need to be able to work as a society to try and make things better and not create extra barriers for people. It just doesn't feel like a supportive environment at the moment.

Continuing her job search, she said “I've had some very positive past experiences and some really negative ones. So I just try and approach it with goodwill, I suppose. But cautious at the same time.”

Mental Health Awareness Week in the UK is Mon, 12th May – Sun, 18th May 2025.

The Pathways to Work Green Paper is open to consultation until 30th June.

Statistics from the Labour Market Survey have experienced reliability concerns in recent years due to falling survey response rates.